Strong winds and big waves battered Douglas all day. Before the rest day, the atmosphere was tense – nobody wanted to lose. It resulted in several draws, but some players could not stand the tension. Evgeny Najer blundered in an equal position to lose to Fabiano Caruana, while Javokhir Sindarov destroyed Samuel Sevian’s queenside, where the opponent’s king was hiding. A dramatic win by Anna Muzychuk in a drawn queen endgame against Bibisara Assaubayeva allowed her to take over the sole lead, as her main rivals could only manage draws.

There was a big surprise in the opening on board one. Andrey Esipenko had a won position against Hikaru Nakamura at the FIDE Grand Prix in Berlin in 2022 when Nakamura played his usual Giuoco Piano, though that game ended in a draw. Nakamura has met Esipenko’s 1.e4 with 1…e5 in all the games they’ve played so far, but in the sixth round of the FIDE Grand Swiss, he surprised his opponent with 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 g6.

Nakamura tested the Accelerated Dragon in Qatar Masters to draw with Javokhir Sindarov, but he played it via the 2…Nc6 3.Nc3 g6 move-order. By playing 2…g6 he wanted to avoid the Rossolimo with 3.Bb5, but it allows the Maroczy Bind after c4. These considerations set Esipenko thinking as early as move three!

He went for 3.c3 d5, and then instead of a transposition to the Alapin by taking on d5, he closed the centre with 4.e5. Nakamura developed the knight to c6, and after …Bg7 undermined White’s centre with …f6. This plan has been played by Assaubayeva, Vakhidov, Abdusattorov, Sindarov and Svane, so Nakamura had ample material to work with.

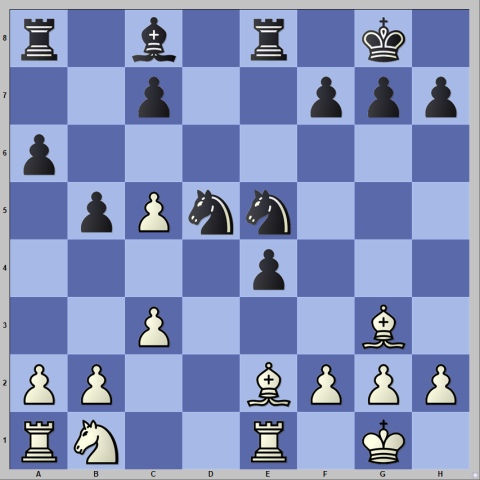

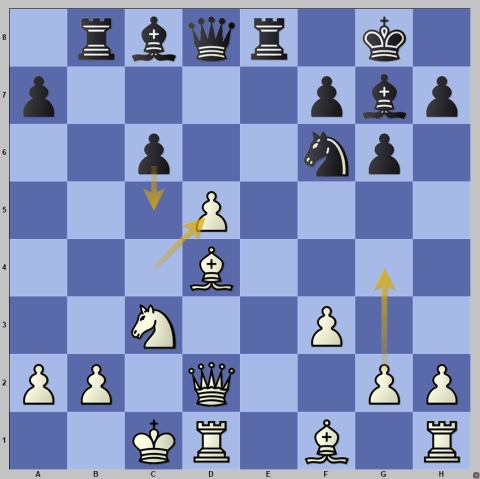

Both players developed, and at the beginning of the middlegame White sacrificed a pawn to open the central files.

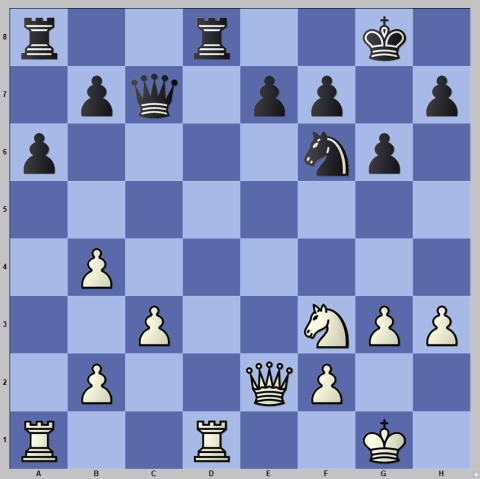

The pawn on g5 is taboo as taking it allows …e7-e5 with tremendous initiative for Black. White played 14.Ne5! Nxe5 15.dxe5 Bxe5 16.Nc3 attacking the pawn on d5 and forcing 16…e6. Esipenko’s compensation consisted of his harmonious development (Black still needs to develop the light-squared bishop), pressure along the central files (especially on the e-file against the backward pawn on e6) and a safer king.

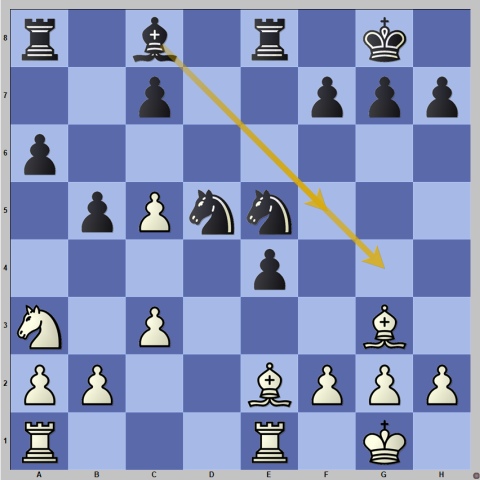

The game ended in a perpetual check at the moment of highest tension.

White is on the verge of clamping down the centre with Bxg6 and Be5, but Black is just in time with 20…e5. Everything is forced now as White must take on g6 and after 21.Bxg6 exd4 22.Qh5 hxg6 23.Qxg6 White delivers a perpetual check.

On board two, Yu Yangyi faced the uncomfortable psychological task of coping with his own favourite opening, the Petroff Defence. Arjun Erigaisi seemed to catch his opponent unprepared. In spite of following a theoretical line, White was spending a lot of time on the known moves.

As usual in such cases, Black demonstrated his perfect opening preparation and effortlessly made a draw by exchanging almost all the pieces by move 22.

After the queens, the queenside pawns were also exchanged, and the draw was agreed on move 30.

On board three, Fabiano Caruana used the same line in the Giuoco Piano Alireza Firouzja played against him at the Paris GCT in 2021 with 5.Bg5.

It would be nice to know whether he was inspired by yesterday’s report and Morphy’s game. His opponent Evgeny Najer seemed surprised, especially as Caruana refined the opening idea by pushing his a-pawn to a5 and then opening the a-file with axb6 when Black played …b6.

The beginning of the middlegame promised a complex game ahead for both players.

The position remained equal, and pieces started to come off. But then, Najer blundered.

Here 25…Qd8 or 25…Re7 would have kept the balance. Najer went for 25…Qa5? allowing 26.Qf3! Re7 27.Nxg6! with a winning position.

In spite of spending eight minutes, Caruana missed this tactic and played 26.Re4, allowing Black to escape out of trouble by 26…f5 or 26…Be6. Najer blundered for a second time with 26…Nf6? And this time, Caruana was ruthless with 27.Nxd7! Nxe4 28.dxe4 Rxe4 29.Qf3, winning two pieces for a rook. White attacks the pawn on f7, so Black was further forced to go into a lost endgame with 29…Qf5 30.Qxf5 gxf5 31.Nb8 with the knight coming to c6.

Caruana converted the advantage and won in 37 moves without allowing any more chances.

On board four, Vladislav Artemiev chose an innocuous line against Alireza Firouzja’s Arkhangelsk Variation. In addition to that, he also spent masses of time on theoretical moves. His choice quickly led to an endgame where Black had little to complain about.

Artemiev managed to keep the pair of bishops. Given his excellent endgame technique, it must have given him some hope. The main problem for both players was the time management – by move 15, they had spent more than an hour, leaving them with a bit more than 30 minutes to reach the time control on move 40.

Black’s free-piece play and space advantage do not allow the white bishops to show their might.

The critical moment arose on move 16.

Black could have played the natural 16…Bf5, but he went for the pawn sacrifice with 16…Bg4 instead.

After 17.Bxe5 Bxe2 18.Bxc7 Bd3 he hoped that the opposite-coloured bishops, his strong bishop on d3 and the possibility to advance his kingside pawns would provide enough compensation, but Artemiev played extremely well to neutralize these factors and obtain a winning position.

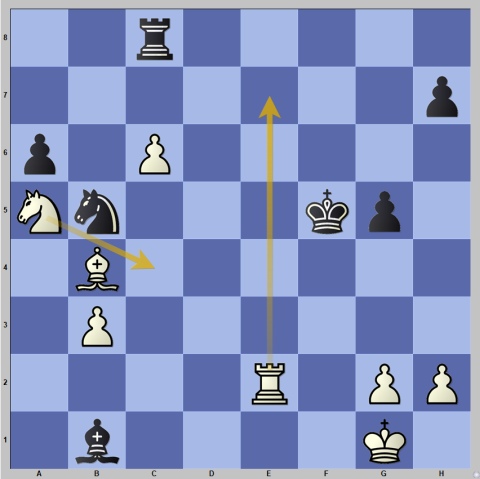

However, in severe mutual time trouble, Artemiev made a decision that is hard to explain.

Instead of the natural 36.Re7, Artemiev abandoned the jewel of his position, the passed c6-pawn on c6 35.Nc4? to go for the pawn on g5 after 36…Rxc6 37.Re5 Kf6 38.Be7 Kf7 39.Bxg5, but it was an unequal exchange.

Black activated his rook with 39…Re6-e2 and obtained enough play for a draw.

White tried to make something of his extra pawn, but the best chance for that was long gone.

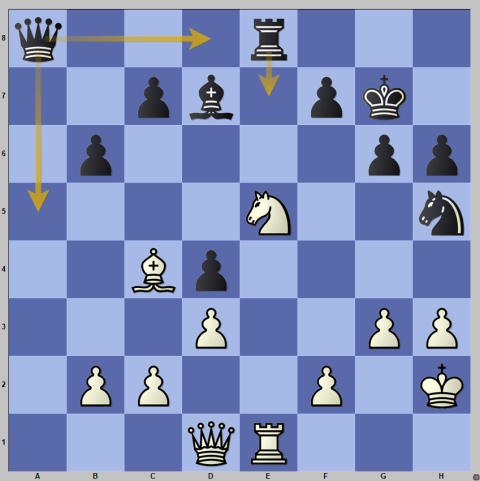

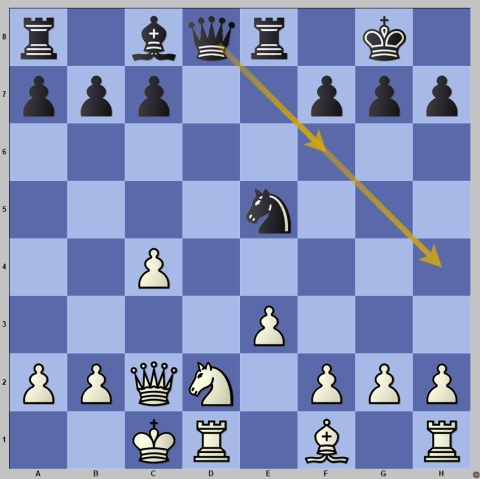

Javokhir Sindarov won a fierce attacking game with the black pieces against Samuel Sevian. In a King’s Indian structure, White castled queenside but was hit with a series of blows, similar to the strong waves that crashed against the shore in Douglas.

The first one came early.

Black executed the typical central strike with 9…d5, obtaining free piece play.

The second one came in a position that was already very dangerous for White.

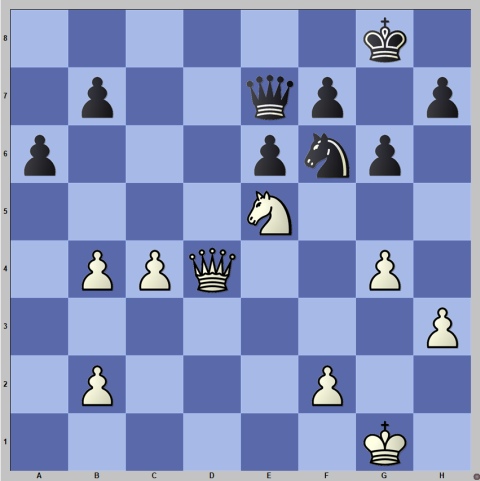

According to Sindarov, White’s last move 14.cxd5, was the decisive mistake. In his opinion, White had to play 14.g4 with the idea of g5 to exchange Black’s dark-squared bishop, but even then, Black has a dangerous initiative.

The exchange on d5 was met with the excellent 14…c5! 15.Bxc5 Qa5, and visually it was clear that Black’s attack must prevail.

Black didn’t shy away from material sacrifices.

When attacking, the most important thing is to get to the king. Hence, 17…Rbc8! 18.gxf5 Nxd5 and the catastrophe on c3 was inevitable. Black won in five more moves.

A true storm on the board, mirroring the storm that battered the Isle of Man during the entire day.

Two opening experiments in Round 6 are worth noting.

Facing Radoslaw Wojtaszek with the black pieces, Erwin L’Ami, known for his fundamental approach to opening preparation, chose the unbelievable Albin Countergambit! Such a questionable opening is not played on this level! It certainly never occurred to Wojtaszek that this opening could happen, so the surprise was complete. He spent a lot of time and couldn’t recall his preparation, as on move ten, he came up with a novelty.

Here the move 10.Bd2 is known to be strong. White allows Black to regain the pawn but exchanges queens in the process and remains with the bishop pair in the endgame with a stable advantage. Wojtaszek played 10.Qc2 – not a bad move at all, but it kept the position more complex, thus giving Black more practical chances.

Black did obtain decent compensation, but in the following position, he allowed a strong knight maneuver.

Here, Black should have played 14…Qh4 and after 15.Nf3 Nxf3 16.gxf3 Bh3 (or 16…g6) White’s pawn weaknesses on the kingside won’t allow him to convert the extra pawn.

However, L’Ami played 14…Qf6? but missed the very strong 15.Ne4! Qc6 16.Nc3 with Nd5 next, which cemented White’s control over the center. Radoslaw continued with Be2 and Rd4, to further strengthen his central grip. In addition to the extra pawn, this gave him a big advantage.

Black tried to free himself with a tactical sequence, but this only led to a lost rook endgame. The following position is very instructive, showing the importance of control of the vital open file.

White penetrated to the seventh rank with Rd7 and then marched his king to c5. With a cut-off king along the d-file, Black was doomed. He resisted as well as he could for more than 70 moves, but Wojtaszek didn’t let the win slip.

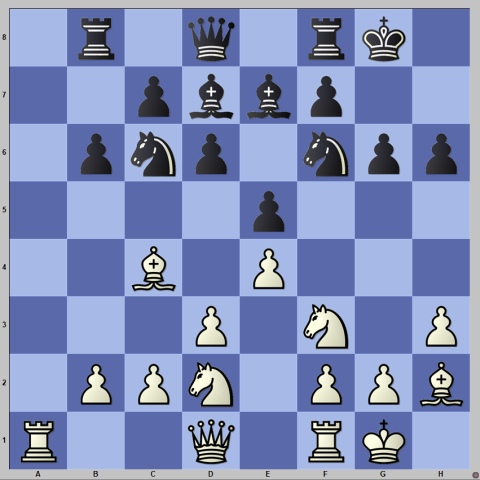

The fertile mind of Jorden van Foreest is never at rest. Facing Benjamin Gledura’s Najdorf, he uncorked another unexpected idea.

In this standard position, White played 7.g4!? giving up a pawn, seemingly for nothing. Gledura took it and after 7…Nxg4 8.Rg1 h5 9.h3 Ne5 10.Qg3, the position was messy and unclear where the engine was giving White some advantage in spite of the pawn deficit!

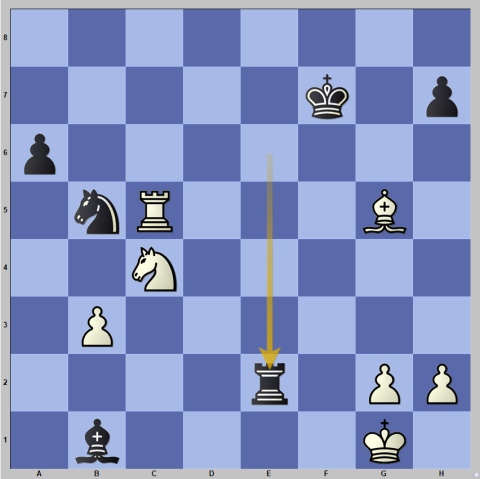

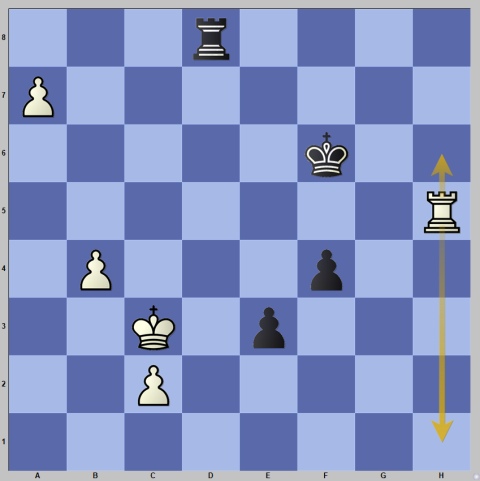

White’s compensation was enough to regain the pawn, and even though Black managed to exchange queens and transpose to an endgame, Jorden still held an advantage. He built it up to a winning one, but then misplayed the position and allowed Black to come back into the game and reach equality. The endgame was still sharp and tactical, and it liquidated to a position where White had three passed pawns, and Black had two. Perhaps to his disbelief, it was Whtie who had to be more careful in this endgame.

The only (!) move to save the game is 54.Rh1! f3 55.Rf1! f2 56.a8Q (deflection) Rxa8 57.Kd3 and White manages to blockade the pawns.

Despite having a lot of time on the clock, Van Foreest didn’t manage to figure out what was necessary and gave a check with 54.Rh6+? which after 54…Kf5 followed by …Ke4, only helped the black king to support the passed pawns. As the saying goes, Black’s pawns run faster.

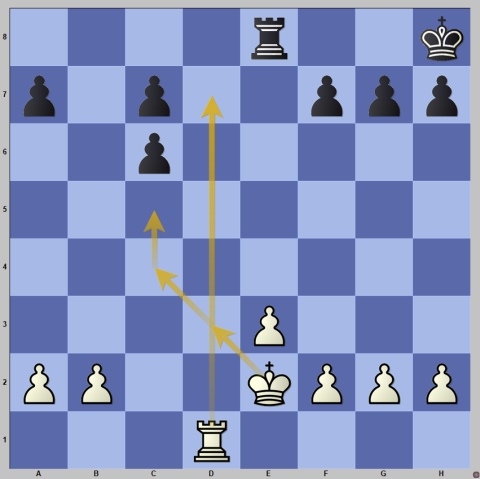

In the game between Axel Bachmann and Bassem Amin, we were reminded of the somewhat forgotten art of the king walk.

Black played the remarkable 11…Kd7!! Intending to switch the position of the king and the queen. The king marched to c7 to enjoy the safety of the queenside, while the queen went to g7 via f8 to replace the departed dark-squared bishop and control the long diagonal.

The game was very sharp and eventually ended in a perpetual check on c6 and b6, though it has to be added that both sides missed their best chances before that.

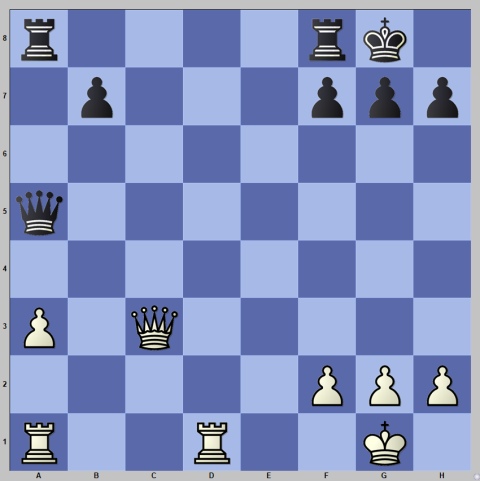

On board one in the women’s section, Anna Muzychuk employed the Alapin Sicilian facing Bibisara Assaubayeva’s Sicilian. White has an excellent record in the line they followed, but the engine’s evaluation is more modest, giving White only a tiny advantage. This was borne out in the game as Black managed to simplify and equalize. It seems that White could have been a bit more precise to pose more serious problems. By move 21 the following position was reached.

With imminent exchanges on the d-file, the only pieces left on the board were the queens and the knights.

White tried to make something out of her queenside pawn majority, and eventually, the game went into a queen endgame where White had a passed b-pawn.

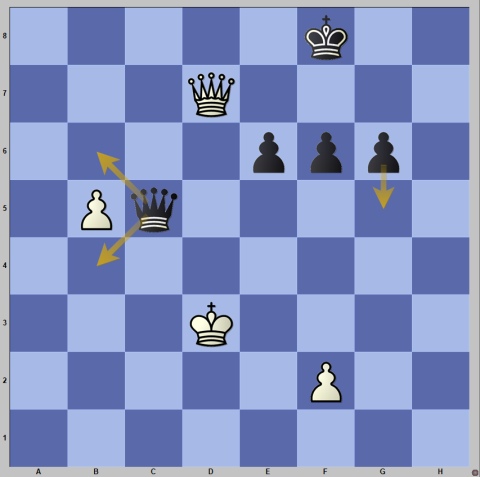

Black’s extra pawn is irrelevant, as she cannot create a passer with her three pawns on the sixth rank. The position is objectively drawn, but Black is on the defensive, and here she should have played 50…Qb4 (to prevent the white king from approaching the passed b-pawn), though other moves like 50…g5 or 50…f5 were also possible.

Black played 50…Qb6?? instead, allowing 51.Kc4! and suddenly Bibisara was lost! Having realized what she’d done, Assaubayeva played 51…g5, allowing 52.Qd4! when Black either exchanges queens with the b-pawn then promoting, or allows Qxf6xg5 when she loses her kingside pawns.

The conversion of White’s advantage wasn’t too difficult.

It was an incredibly important victory for Anna Muzychuk to take over the sole lead before the rest day.

The game on board two between Vaishali Rameshbabu and Aleksandra Goryachkina was a balanced Giuoco Piano where neither side wanted to take unnecessary risks. The calm game ended in a draw in 41 moves.

On board three Leya Garifullina faced Tan Zhongyi. Black deviated from her usual repertoire by choosing the Philidor Defence, something she had never done before. Garifullina reacted well, keeping control of the position and obtaining an advantage, but then both players started to play very fast, and this cost White several opportunities to increase her advantage. As a result, it petered out to a drawn rook and later pawn, endgame.

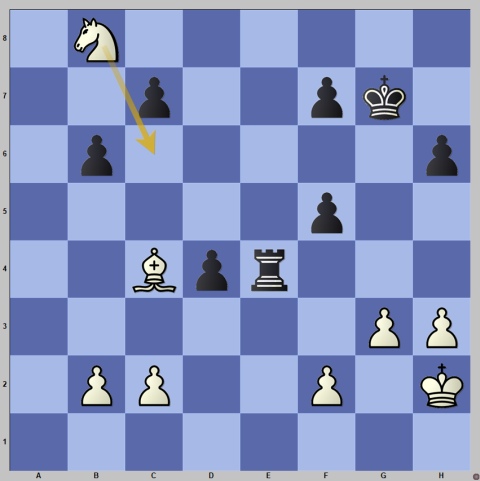

On board four Marsel Efroimski and Batkhuyag Munguntuul played a long theoretical line in the Taimanov Sicilian. On move 18, White was faced with the most common problem of modern preparation – memorization of one’s analyses.

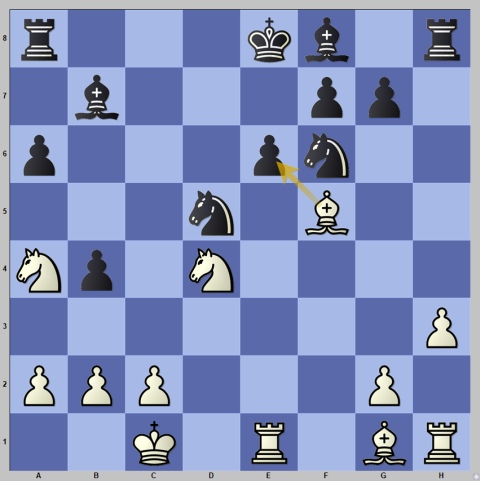

In this position, the only move for White to continue to fight for the initiative and the advantage is the already played 18.Be4! White scores over 80% in this position after 18…Be7 19.Qe1.

It is the moment where Marsel’s memory failed her. She went for 18.dxe6?! dxe6 19.Qe1 (here you see the likely culprit – the move Qe1 features in the correct variation, but White couldn’t figure it out over the board), but after the exchange of queens, it was already Black who was playing for an advantage.

Unwilling to suffer in an inferior endgame, White continued in typical sacrificial style in spite of the absence of queens on the board. After 19…Qxe1 20.Rxe1 Ng4 21.Bf5 Ngf6

White played 22.Nxe6! fxe6 23.Bxe6, which gave her sufficient compensation, but more importantly, this sacrifice changed the course of the game – instead of nursing a positional advantage in an endgame by technical means, Black was now forced to calculate lines and play in middlegame fashion.

There were mutual inaccuracies in this very complex endgame, with the decisive moment coming right after the time control.

Instead of keeping the pieces on the board with 41…Ke8 or 41…Kd6, when she would have had excellent winning chances, Black allowed the simplifications with 41…Kc6? 42.Rxe7 Rxa6 43.Re6 Kb7, and after the exchange of rooks and bishop for the knight on c3, White made an easy draw as her pawns distracted Black’s forces while the white king went to capture the last black pawn.

As many as nine players – Fabiano Caruana, Hikaru Nakamura, Andrey Esipenko, Alexandr Predke, Javokhir Sindarov, Arjun Erigaisi, Yu Yangyi, Gujrathi Vidit and Radoslaw Wojtaszek – are now tied for first place going into the rest day.

In the women’s section, Anna Muzychuk leads alone with 5 out of 6 and is followed by four players half a point behind: Aleksandra Goryachkina, Rameshbabu Vaishali, Bibisara Assaubayeva and Antoaneta Stefanova.

Fans can follow the Grand Swiss 2023 by watching live broadcasts of the event on FIDE Youtube and Twitch with expert commentary by GM David Howell and IM Jovanka Houska.

Round 7 starts on November 1 at 14:30 PM local time.

Written by GM Alex Colovic

Photos: Anna Shtourman, John Saunders

Official website: grandswiss.fide.com

About the event:

The FIDE Grand Swiss and FIDE Women’s Grand Swiss 2023 takes place from the 23rd of October to the 6th of November at the Villa Marina, Douglas, Isle of Man.

Both tournaments are part of the qualifications for the World Championship cycle, with the top two players in the open event qualifying for the 2024 Candidates Tournament and the top two players in the Women’s Grand Swiss qualifying for the 2024 Women’s Candidates.

Eleven rounds will be played under the Swiss System, with 164 players participating from all continents: 114 in the Grand Swiss and 50 players in the Women’s Grand Swiss.

The total prize fund is $600,000, with $460,000 for the Grand Swiss and $140,000 for the Women’s Grand Swiss.

The first Grand Swiss was held in 2019 in the Isle of Man and was won by GM Wang Hao, who scored 8/11. The 2021 edition was moved from Isle of Man to Riga due to Covid restrictions on the island and was won by GM Alireza Firouzja.

This is the second time that a Women’s Grand Swiss event will be held. The inaugural edition in Riga was won by GM Lei Tingjie.