The number of draws on the top boards doesn’t tell the whole story of hard-fought games, with plenty of interesting opening ideas and spectacular sacrifices. Fabiano Caruana essayed a rare move in the Semi-Slav tabiya, while Hikaru Nakamura hoped for inspiration by employing Bobby Fischer’s favourite variation against the Sicilian Defence. Santosh Gujrathi Vidit spotted an incredible tactical shot to beat Javokhir Sindarov and emerge as the sole leader as his friend Arjun Erigaisi couldn’t break Andrey Esipenko’s defence in an epic battle that lasted for 90 moves. In the women’s section, the draw on board one between Aleksandra Goryachkina and Anna Muzychuk meant that victories by Rameshbabu Vaishali and Antoaneta Stefanova (against Bibisara Assaubayeva and Mariya Muzychuk, respectively) allowed them to join the lead to form a trio at the top.

The opening surprises were in no short supply on the top boards in Round 7 of the FIDE Grand Swiss.

On board one, Radoslaw Wojtaszek played Fabiano Caruana and, just like in his round four game against Anish Giri, faced an opening he prepared together with Anand’s team in 2008 for the match against Vladimir Kramnik.

In that match, the Semi-Slav (and the subsequent Meran) was Anand’s main defence against 1.d4, bringing two invaluable victories on the way to winning the title. Caruana doesn’t play the Semi-Slav often, so his choice was aimed at forcing his opponent to recall lines he hadn’t looked at in his pre-game preparation. The Semi-Slav is a fighting choice, so Caruana showed his aggressive intentions early on. He also introduced an early twist.

In the tabiya of the Semi-Slav, Caruana went for a less common move.

In this position, the most common move for Black is 8…dxc4 (played by Anand many times, where he demonstrated several ideas from their preparation), but there are also moves like 8…e5, 8…h6 or 8…Qe7.

Caruana played 8…Re8, the move recently employed by the young talents Samuel Sevian and Mittal Aditya.

Wojtaszek likes to think, and this move gave him something to mull over. He followed the theoretical path, but by move 14, Caruana had a 40-minute advantage on the clock. In addition to that, he also introduced a novelty on that very move.

There are several computer games from this position, and in all of them, Black played 14…Bc7, but Caruana preferred 14…Nge5. After the exchange of knights, Wojtaszek retreated the bishop to e2. Needless to say, Caruana was still well into his preparation as Wojtaszek had less than an hour to reach move 40.

The ensuing middlegame was balanced. White advanced his central majority with f4 and e5, to which Black replied with …f6-f5, establishing a blockade on the e6-square. At first sight, it may appear that the protected passed pawn gives White a solid advantage, but in fact, this blockade, which can also happen from some lines of the Berlin, is known to effectively neutralize White’s extra pawn on that side of the board.

Here’s an illustration of Black’s blockade. White cannot make any progress. The queens were exchanged, and then Black advanced with his own pawn majority.

Fabiano made certain progress and even managed to exchange his a-pawn for White’s b-pawn, thus creating a passed pawn on the c-file. He advanced this pawn as far as c3, but this still wasn’t enough to tip the balance. The following position was reached after Black’s 60th move.

Draw was agreed one move later.

On board two, Hikaru Nakamura faced the Four Knights Sicilian against Alexandr Predke. This variation, which arises after 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 e6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 has become very popular for several reasons: one is that it allows Black to avoid the Rossolimo by playing 2…e6, and the second is that after 6.Ndb5 Black can choose between the Sveshnikov Sicilian with 6…d6 7.Bf4 e5 8.Bg5 a6 or the very safe line 6…Bb4, third is that the complications after 6.Nxc6 bxc6 7.e5 Nd5 works nicely for Black.

Therefore, it’s not a surprise that many players have chosen to avoid all of the above with moves like 6.Be2 or 6.a3, the latter one chosen by Nakamura.

The little pawn move stops the pin with …Bb4, but this tempo allows Black to transpose to the Scheveningen setup where the move a3 isn’t strictly necessary. Nakamura’s twist came two moves later.

Instead of the usual Scheveningen setup with 8.Be2 Hikaru chose the Sozin Attack with 8.Bc4.

The Sozin was a fearsome weapon of the great Bobby Fischer. He was attracted to it because of the simple and straight-forward positional idea – White’s bishop on the a2-g8 diagonal is blunted by the pawn on e6, so White simply plays f4-f5 to attack that pawn, and in case of …e5, the diagonal for the bishop is opened and the bishop becomes a very strong piece.

Modern theory hasn’t been kind to the Sozin Attack, as reliable defensive methods for Black have been found. Even Fischer gave up on it after the fourth game in his match with Spassky in Reykjavik in 1972 when Spassky countered it in a very effective fashion. And yet, here we are in 2023, and we see another American resurrect the fearsome weapon of his predecessor.

Fischer had a lot of quick wins in his pet line by employing the f4-f5 advance and then using the weakened d5-square for his pieces. This was mostly because his opponents didn’t know how to react to this plan. Nowadays, Black players know what to do, and Predke wasn’t an exception. While White did take control over the d5-square, he had to give up something in return – in this case, the dark-squared bishop.

Black obtained an excellent position thanks to his control of the dark squares, with the dominant bishop on e5 being the key piece. After White took the pawn on b7, Black responded with …Rb8 and took on b2. The position was heading to mass simplifications and a draw, but inaccuracies crept into Predke’s moves, and somewhat unexpectedly, White won a pawn.

White didn’t really have realistic winning chances, but a pawn is a pawn, and he could press for a while without any risk.

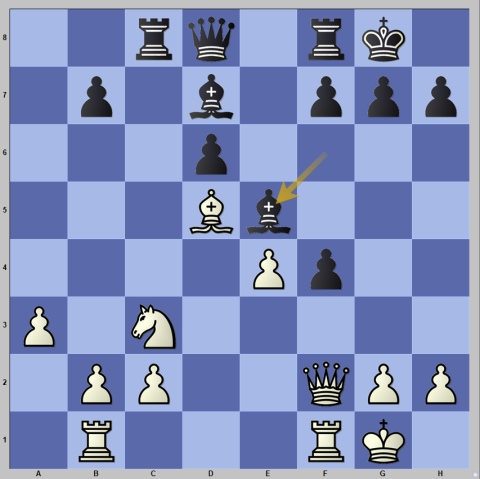

Predke centralized his king on e5 and sought counterplay on the kingside, while White exchanged the bishop and pushed the c-pawn further. The ensuing rook endgame was drawn and ended in a curious stalemate featuring a desperado rook.

White’s last move was 47.g3, which allowed Black to start checking and giving up his rook with 47…Rc2+ 48.Kg1 Rg2+ and further checks along the second rank.

On board three, Javokhir Sindarov chose the Giuoco Piano against Santosh Gujrathi Vidit. As the name suggests (“quiet game”) things unfolded slowly, but it appeared that White didn’t have a major idea in the opening. As early as move 11, Black achieved the central push …d5.

Instead of advancing in the centre with 11.d4, which would have been countered by 11…Ng6, White played 11.Nh4, with the intention to meet …Ng6 with Nf5, but with the knight no longer latching onto the pawn on e5, Black could play the liberating 11…d5.

After 12.exd5 Nexd5, White had the semi-open f-file, but Black’s good central control ensured that he had good play.

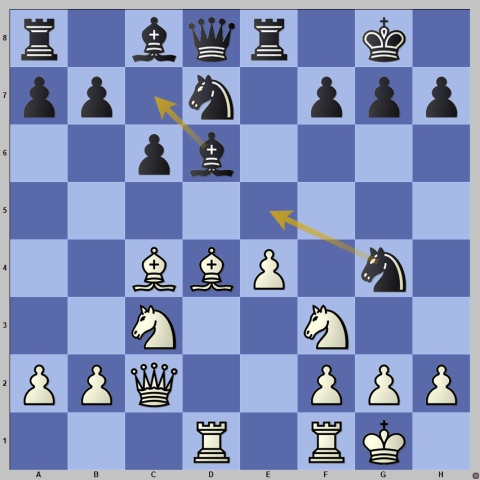

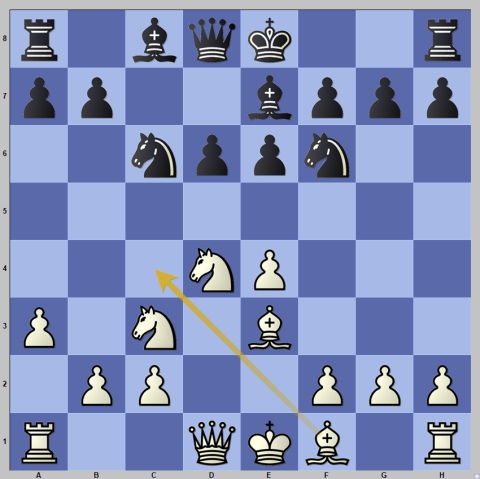

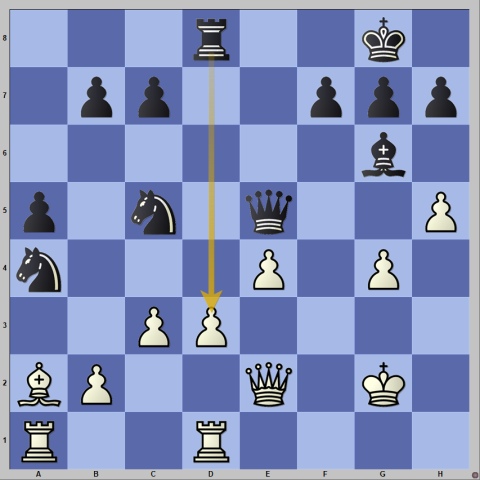

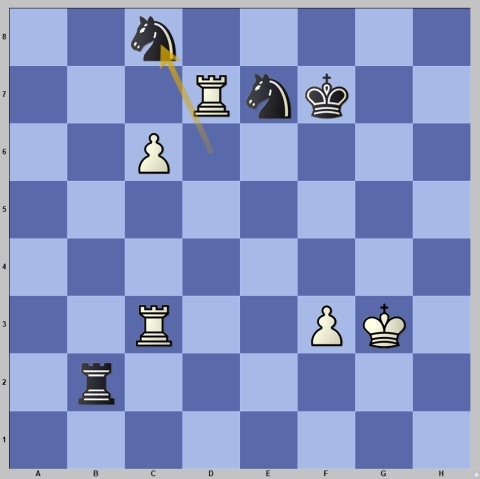

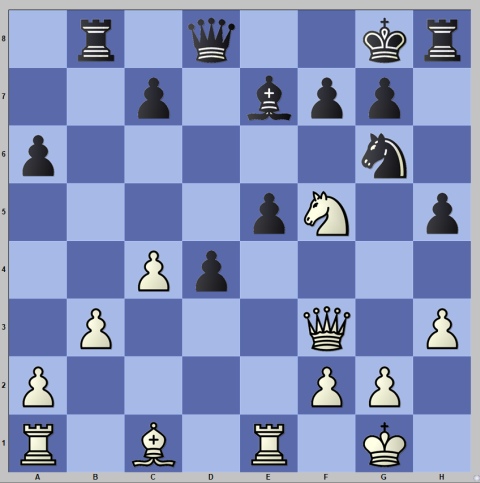

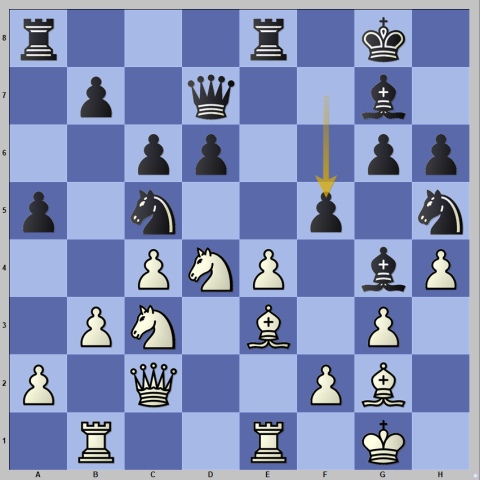

The game was in the balance until Sindarov initiated a forcing sequence where he missed a killer tactic.

It appears that White has everything under control, winning the bishop on g6, but what he missed was the spectacular 27…Rxd3!! that immediately decides the game in Black’s favour.

The point of the combination is that the rook on d3 is taboo in view of 28.Rxd3 Nxd3 with threats of …Nf4 or …Bxe4, while taking the bishop on g6 is met by …Qg3, where White is either mated or loses too much material.

Visibly shocked, Javokhir played the desperate 29.Bxf7. Black was spoilt for choice of how to win, either by taking that bishop or moving the king. Vidit decided to play 29…Kf8 and ended up with two pieces for the rook and a winning endgame after the exchange on d3 and picking up the pawn on e4 with the queen.

White resisted until move 57, but the result was never in doubt.

An extremely important win for Vidit, who became the sole leader after seven rounds.

On board four, Arjun Erigaisi emerged as a clear winner of the opening duel with Andrey Esipenko. In modern chess, this doesn’t mean that there is an advantage or even an initiative, but rather that the player has managed to impose his opening preparation on his opponent.

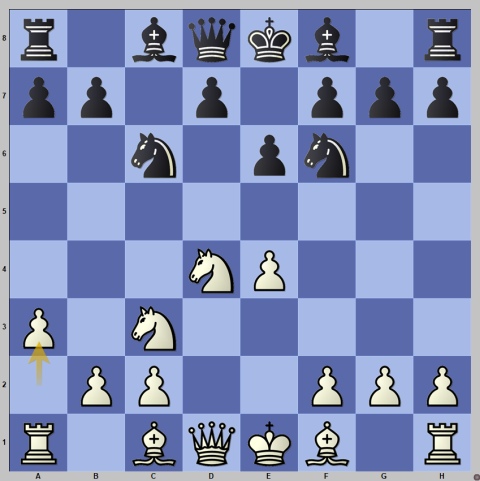

In a popular line of the Anti-Marshall with 8.h3 Bb7 9.d3 d5 10.exd5 Nxd5

White played the topical 11.Nbd2, as the alternatives 11.Nxe5 and 11.a4 don’t seem to promise much at the moment. After 11…Qd7 12.a4 Esipenko deviated from the recent game Erigaisi-Keymer, played in July at the tournament in Biel, with the move 12…Rae8 instead of Keymer’s 12…Nf4.

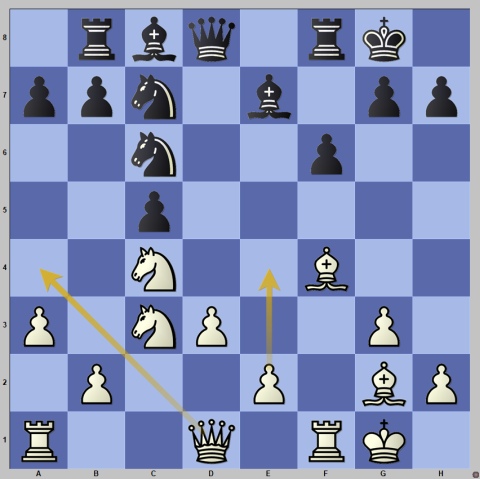

It was Erigaisi’s 15th move that set Esipenko thinking for 16 minutes.

In this position, White usually moved the c-pawn for one or two squares, but Erigaisi came up with the novelty 15.Bd2.

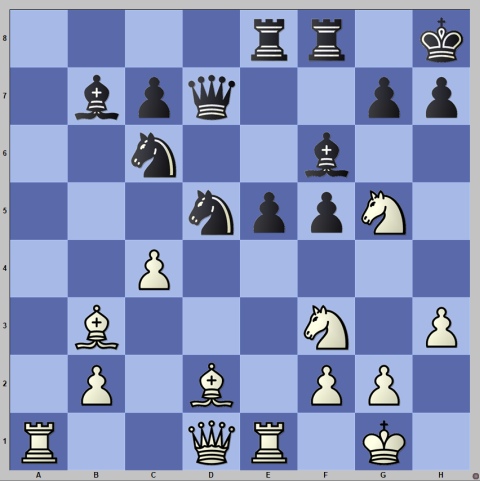

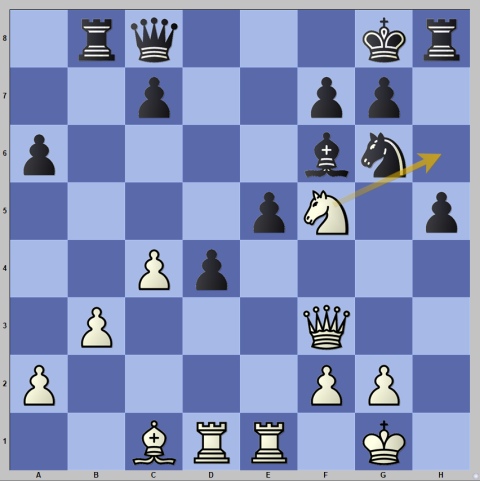

Four moves later, Esipenko had one hour (!) less on the clock, frantically calculating the complications in the following position.

White’s main tactical idea is the move c5, when the weakness of the f7-square can be exploited by Nf7. Objectively Black is still fine, but it was obvious that Esipenko had to calculate everything over the board while Erigaisi was still in his preparation.

The complicated lines both players needed to calculate were numerous, but they kept the level of their play incredibly high. In the following position, Esipenko found the only move to stay in the game.

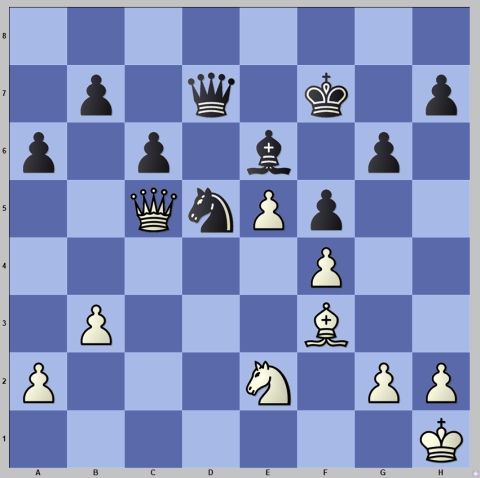

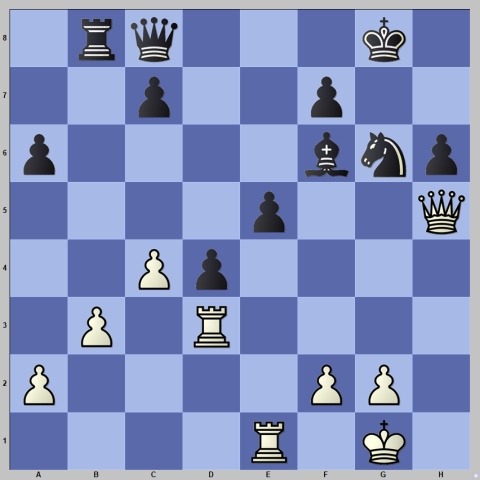

Black came up with 24…e3!, which forced an unbalanced endgame after 25.Bxe3 Qxd1 26.Rad1 h6 27.Rxd7 hxg5 28.Rxc7 Ba8:

White has a rook and two pawns for two light knights. The position is dynamically balanced because, with so many pieces on the board, it’s not easy for White to advance his two connected passed pawns. Nevertheless, it’s easier to play with White since he has a clear plan to find a way to advance the pawns, while Black’s play is based on preventing that.

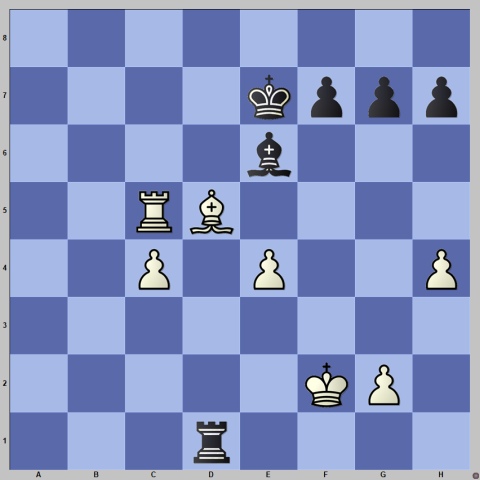

The time control was reached in the following position.

The blockade looks strong, but Black is still passive. White kept pushing, and pieces were exchanged. By the second time control, all Black’s pawns were gone, but he kept his knights.

Black’s blockade was still firm, and barring a blunder, a draw seemed a logical outcome. The blunder never came and a draw was agreed on move 90.

Important wins in this round were scored by Vincent Keymer (against Anton Korobov), Bogdan-Daniel Deac (against Nodirbek Yakubboev) and Yuri Kuzubov (against Vladislav Artemiev), Etienne Bacrot (against Yu Yangyi) and Vladimir Fedoseev (against Ramazan Zhalmakhanov, his first loss in the tournament!).

All these players, together with Fabiano Caruana, Hikaru Nakamura, Radoslaw Wojtaszek, Alexandr Predke, Arjun Erigaisi and Andrey Esipenko, are sitting on 5/7, only half a point behind the leader.

In the women’s section, on board one Aleksandra Goryachkina allowed an exchange against Anna Muzychuk’s Ruy Lopez that is usually frowned upon.

With her last move, Black defended the e5-pawn and now threatens …b5 and …Na5 to exchange White’s valuable light-squared bishop. Therefore, White plays 7.c3 in this position to safely retreat the bishop to c2 in case it is attacked.

After spending four minutes on her move, Goryachkina played the surprising 7.h3, allowing 7…b5 8.Bb3 Na5, when Black managed to exchange her knight for the dangerous bishop. This exchange is in Black’s favour, and it’s strange that Goryachkina allowed it. White is not worse after it, but can hardly play for an advantage anymore and the long-term perspectives are better for Black, who now has the bishop pair.

As the game progressed, it appeared that Black wasn’t very ambitious and used the advantages of her position to ensure that she was safe. The open d-file led to exchanges, and the final precise move for Black was played in a queen endgame.

With 31…Qe4! Black made sure that her active queen prevented White from even dreaming about making use of Black’s doubled b-pawns. A draw was agreed three moves later.

On board two, Bibisara Assaubayeva stuck to her usual repertoire as of late and played the English Opening with White. Rameshbabu Vaishali responded with an ambitious line, establishing a Maroczy bind in the centre. The critical position arose on move 14.

White played the thematic move f4 to exchange the space-grabbing pawn on e5 and has a comfortable piece play in exchange for Black’s better pawn structure (Black has two pawn islands compared to White’s three). Here, the best was 14.Qa4, to put serious pressure on Black’s queenside, especially the knight on c6.

However, Assaubayeva played the positionally questionable 14.e4?! which shut her own bishop on g2 and weakened the d3-pawn and the d4-square. Black quickly grabbed initiative after 14…Rc8 followed by …Ncd4, while White’s control over the d5-square (and the knight that landed there) was not enough to compensate for the created weaknesses, thus giving Black a stable advantage.

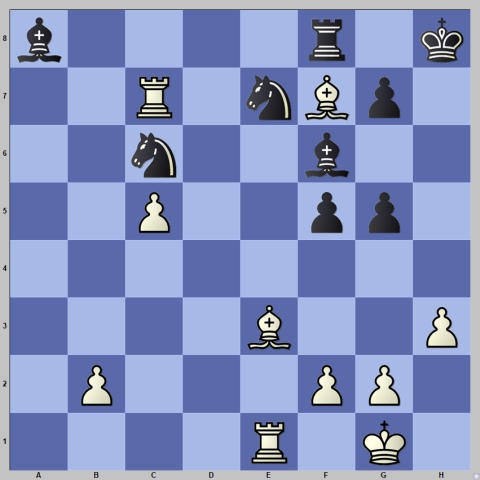

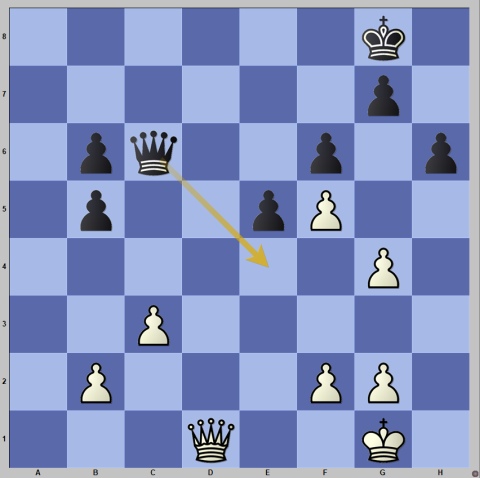

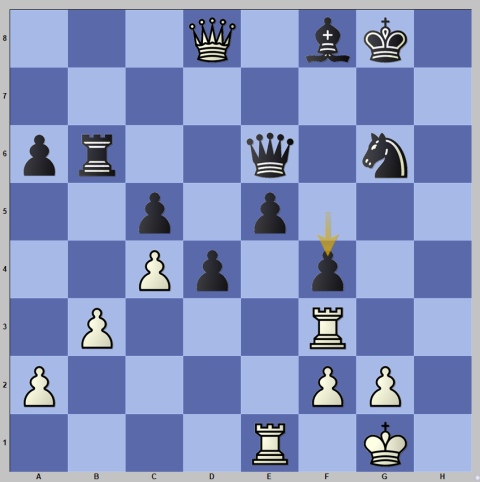

Still, thanks to the strong knight she established on d5, White continued to play normally, and the logical developments were disrupted on move 30.

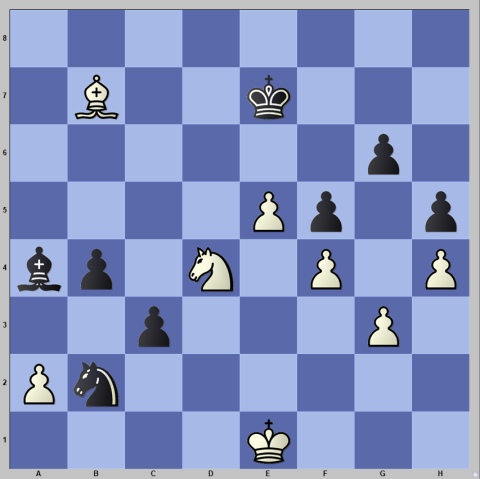

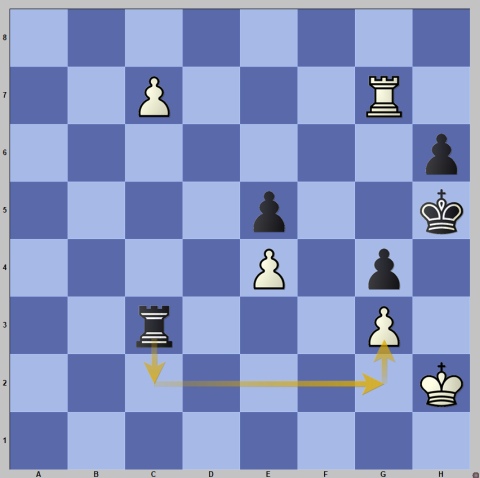

Here Black missed her opponent’s threat, which she could have prevented with 30…Kf7, and played 30…Qa7 missing 31.Nxf6! with White winning a pawn. The ensuing endgame after the exchange of queens was objectively drawn, but it still contained some danger for White. This time it was her turn to miss an important resource.

White’s desire to bring the king to the centre was understandable, but she had to start with 36.Bf3, as 36.Kg1?? allowed 36…Bd4! and all of a sudden, White couldn’t stop the b-pawn because of the pin!

The b-pawn cost White a piece and the game. With the opposite-coloured bishops on the board, Black had to demonstrate some technique, but Vaishali was up to the task and won the game.

On board three Mariya Muzuchuk sacrificed a pawn early on against Antoaneta Stefanova. In the Steinitz Deferred variation in the Ruy Lopez Black chose a rare option on move six.

The usual moves for Black are 6…Nf6, 6…g6 or Be7, but Stefanova chose 6…Bg4, a thematic move that aims to exchange the knight controlling the weakened d4-square. White replied energetically with 7.d4 exd4 8.Re1, which looked promising, but Mariya misplayed later on and allowed Black to keep the pawn while consolidating her position at the same time.

After 19 moves, Black’s only problem was that she had only 19 minutes to reach move 40.

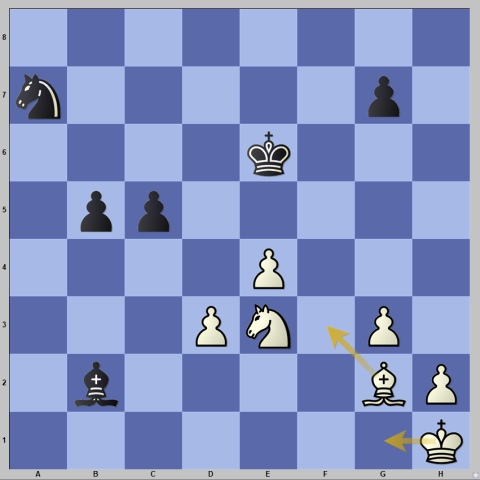

Black is inconvenienced by the uncastled king and the rook being stuck on h8, but her extra pawn and excellent central control more than compensate for those factors. White’s only hope was the sharpness of the position and Black’s questionable time management.

Seeing no compensation for the pawn, Muzychuk tried to muddy the waters by first sacrificing another pawn and then two pieces for a rook.

White played 26.Nh6 Rxh6 27.Bxh6 Nh4! (removing the queen from the square from where she attacked the bishop on f6) 28.Qxh5 gxh6 29.Rd3 Ng6, but this led to a won position for Black as White couldn’t create any threats.

Stefanova managed to reach the time control without spoiling her position and then she could take some time to ensure that the win didn’t slip. Black’s 40th move was 40…f4.

On board four a very complex Fianchetto King’s Indian appeared on the board in the game between Tan Zhongyi and Stavroula Tsolakidou. In a relatively standard position on move 14, White made a debatable decision.

With her last move, White could have played Kh2 instead of h4, in order to keep the g4-square covered. Here, the most natural and best was to take control of the g4-square by 16.f3 followed by Be3, when White would have kept control of the position.

Instead, White played 16.Qc2?! and as it often happens in the King’s Indian when White is not careful, Black blasted the position with 16…Qd7 17.Bf4 Nh5 18.Be3 c6 19.Nd4 f5 and the whole board was on fire.

This is what White wants to avoid when playing the King’s Indian. Especially in the fianchetto variation where White should be extra careful and not give up any squares (like the g4-square in this case), which the black pieces can use to launch counterplay, like with …f5 as in the game.

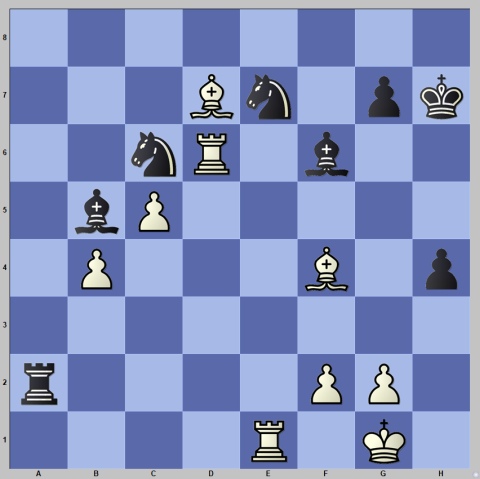

From that moment on, White was on the defensive. The crucial moment was just before the game ended in a draw by repetition.

In this position, Black had the strong move 34…g5! but in order to play it, she had to foresee that after 35.Rb1, she has the unbelievable queen sacrifice 36…Qxb1!! 37.Qxb1 gxf4 where the threat of …e3 rips open the shelter around White’s king. This would have given Black excellent winning chances.

Tsolakidou played 34…Nh5, when White used the chance to escape unscathed by repeating moves 35.Rb1 Qd2 36.Rb2 Qd1.

Vaishali’s and Stefanova’s wins allowed them to join Anna Muzychuk in the lead with 5.7 out of 7. They are followed by Goryachkina and Milliet (who beat Efroimski) on 5 out of 7.

Fans can follow the Grand Swiss 2023 by watching live broadcasts of the event on FIDE Youtube and Twitch with expert commentary by GM David Howell and IM Jovanka Houska.

Round 8 starts on November 2 at 14:30 PM local time.

Written by GM Alex Colovic

Photos: Anna Shtourman, John Saunders

About the event:

The FIDE Grand Swiss and FIDE Women’s Grand Swiss 2023 takes place from the 23rd of October to the 6th of November at the Villa Marina, Douglas, Isle of Man.

Both tournaments are part of the qualifications for the World Championship cycle, with the top two players in the open event qualifying for the 2024 Candidates Tournament and the top two players in the Women’s Grand Swiss qualifying for the 2024 Women’s Candidates.

Eleven rounds will be played under the Swiss System, with 164 players participating from all continents: 114 in the Grand Swiss and 50 players in the Women’s Grand Swiss.

The total prize fund is $600,000, with $460,000 for the Grand Swiss and $140,000 for the Women’s Grand Swiss.

The first Grand Swiss was held in 2019 in the Isle of Man and was won by GM Wang Hao, who scored 8/11. The 2021 edition was moved from Isle of Man to Riga due to Covid restrictions on the island and was won by GM Alireza Firouzja.

This is the second time that a Women’s Grand Swiss event will be held. The inaugural edition in Riga was won by GM Lei Tingjie.