As the fight for the Candidate spots intensified, the players stepped up their efforts. A lot of decisive outcomes on the top boards mean that before the final round, the joint leaders Hikaru Nakamura, Santosh Gujrathi Vidit and Andrey Esipenko have the highest chances of both winning the tournament and securing a ticket to Toronto. In the women’s section, Vaishali R and Anna Muzychuk both won and continue to lead the tournament. The draws by the other players worked ideally for Vaishali, who punched her ticket to the Women’s Candidates with a round to spare.

On board one, the all-American derby quickly went into a position with opposite-coloured bishops. They are generally an early sign of a draw, especially if they come out from a forcing line in the opening. In fact, there was a lot under the surface, and the appearances were deceiving.

Hikaru Nakamura chose to transpose to the Four Knights Scotch facing Fabiano Caruana’s Petroff Defence.

The Petroff was Caruana’s fireproof defence in 2018 when he used it to great effect to win the Candidates tournament and later easily hold against 1.e4 in the World Championship match against Magnus Carlsen.

Nakamura’s choice, the Four Knights Scotch, is an often-used drawing line for two reasons: it leads to relatively simple positions that are easy to play; it is incredibly deeply explored, some lines leading to forced draws.

However, Nakamura’s strategy in the opening was cunning. It had two layers: if his opponent remembered the most precise way to deal with the opening surprise, then a quick and energy-saving draw would be made. But if his opponent failed to do so, then he would obtain a risk-free pressure with a very likely time advantage to boot.

As the game showed, it was the second possibility that happened.

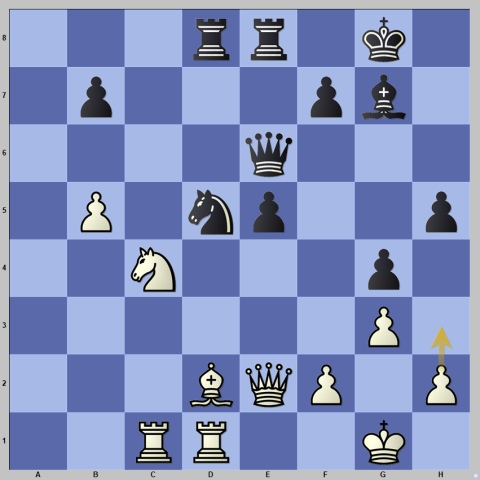

The moment that decided the course of the game was after White’s 12.Rd1

Caruana spent some time recalling his lines and went for the simplifying 12…Bxc3 13.bxc3 Qa5. He could have kept the position more complex with 12…Qe7, but perhaps he thought Nakamura didn’t mind a quick draw (see the first possibility explained above)?

He may have been right in his assumption, but that required precision later on.

As they followed an obscure game played between engines, Caruana committed a mistake that sent the game from a likely possibility number one to a definite possibility number two.

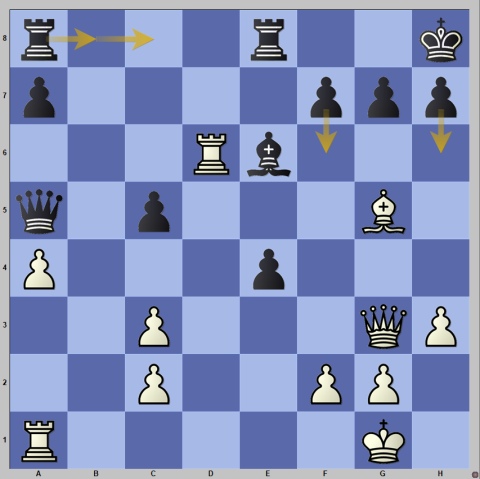

The engine playing with the black pieces chose 18…Rab8, while 18…Rac8 and 18…f6 were also good moves. Caruana played 18…h6? and after 19.Bf4, he was already under severe pressure. His appearance at the board showed great concern about the position.

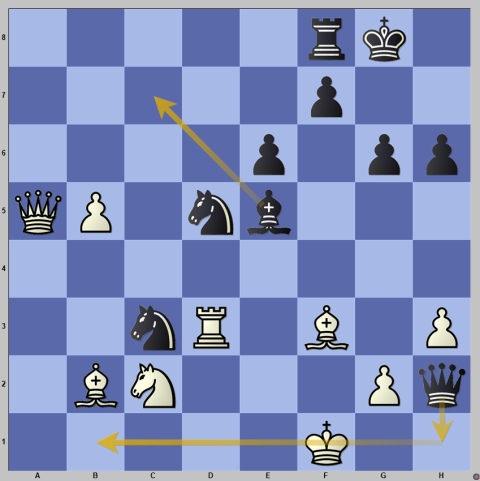

After a further mistake with 19…Re7? (19…Rad8 was best, but even that is hanging by a thread after 20.Be5) White was on the verge of winning after 20.Re1, as Black cannot really defend the pawn on e4. Add to this that Hikaru had more than half an hour advantage on the clock, and you see the triumph of Nakamura’s opening preparation.

Nakamura started to think at this point, and while he didn’t play the absolutely best move 20.Re1, he did make the second-best move in the position 20.Qe3, a tempting option that introduces ideas like Bxh6.

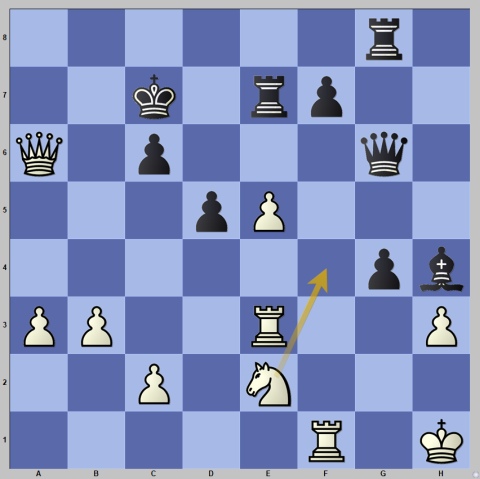

That sacrifice happened later in the game, and coupled with the doubling on the d-file it also gave White a decisive advantage.

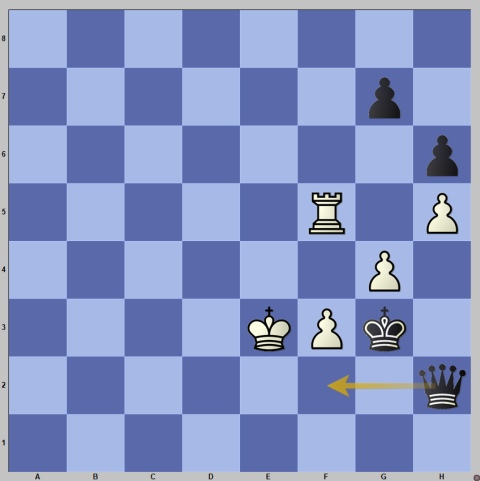

With only eight minutes for 16 moves and his position on the edge of collapse, Black’s situation was not enviable. White continued with 28.Qh4, and soon enough, the attack on Black’s king forced Black to enter a lost endgame.

Black’s rook is hanging, but there is also the threat of Re8 followed by Qg7 mate, so Black was forced to play 31…Qf4, and after the exchange of queens followed by Bg7xf6, White entered a technically winning endgame.

Unlike yesterday, Nakamura didn’t allow any chances and won in 40 moves.

It was an unusual game between elite players when one of them suffered an opening catastrophe. On the other hand, Nakamura won in an identical fashion against the same opponent in the last round of the Norway Chess last June.

On board two Bogdan-Daniel Deac might have been surprised by Vidit Santosh Gujrathi’s choice of the Sicilian after 1.e4. The reasoning is that both players have had an excellent tournament, so as the end draws closer (no pun intended), it makes sense to play more solidly and preserve what has been achieved.

White didn’t go for the open Sicilian and chose the Moscow Variation with 3.Bb5, which was met by the most complex reply 3…Nd7, keeping all pieces on the board. Both the Sicilian and the choice of 3…Nd7 indicated Vidit’s aggressive intentions for this game.

Curiously enough, the position eventually took the shape of Najdorf.

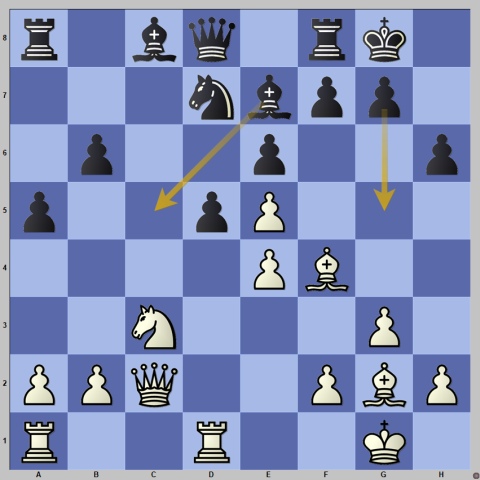

In line with his aggressive mood, Black transferred the knight from c5 via e6 to f4 and then launched a kingside expansion with …g5. This put White under pressure.

White could have played the calm 17.Be2, avoiding the attack with …g4, though Black remains the active side. His 17.Bd2?! lost a pawn to the pretty tactic 17…g4! 18.Be2 Bxe4! With the point that 18.Nxe4 N6d5 pesters the white queen as she can no longer protect the bishop on e2.

White continued with 19.Nf6, but after 19…Bxf6 Black was a sound pawn up.

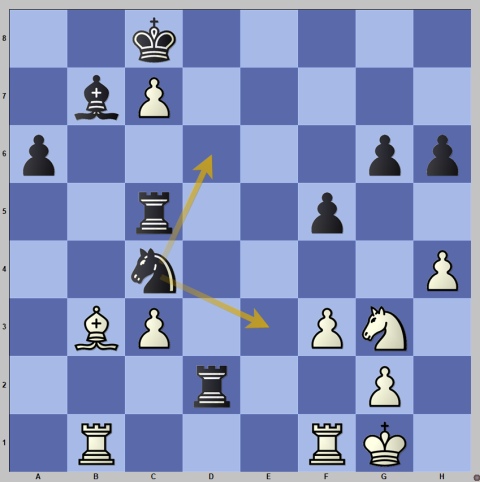

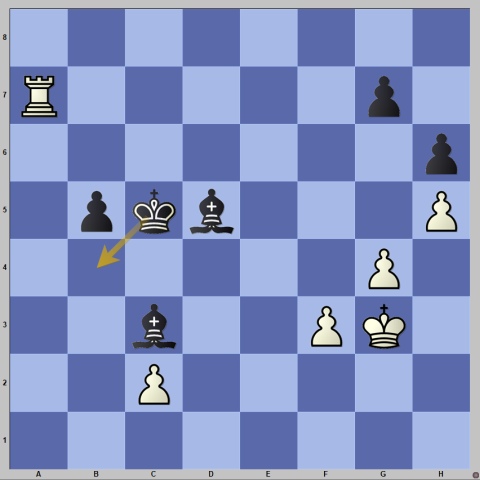

Vidit gradually improved his position while White dug deeply to resist on the kingside. Time trouble also became a factor.

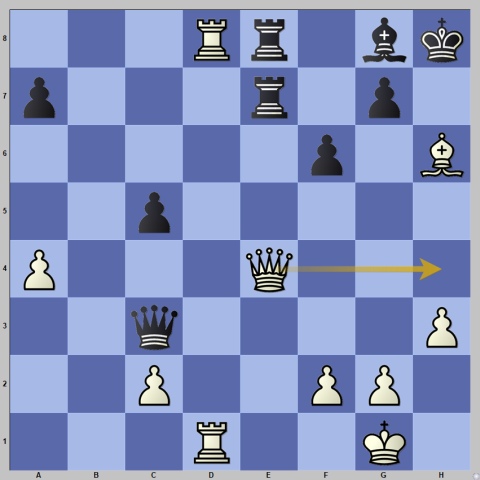

Playing on his last seconds, Deac stirred up trouble on the kingside with 34.h3. Objectively, this isn’t very good, but White didn’t want to just sit and wait while Black was making further progress.

After 34…gxh3 35.Qxh5 Nf6 36.Qe2 Rd4 Black was still in control and remained so when they reached the time control.

White’s last hope was that perhaps he could round up the pawn on h3 but it was dashed by Vidit’s energetic play.

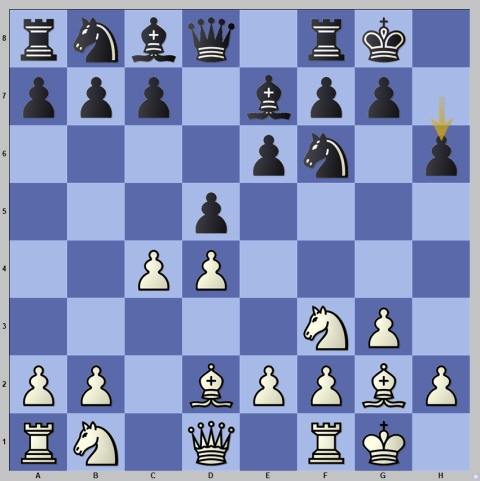

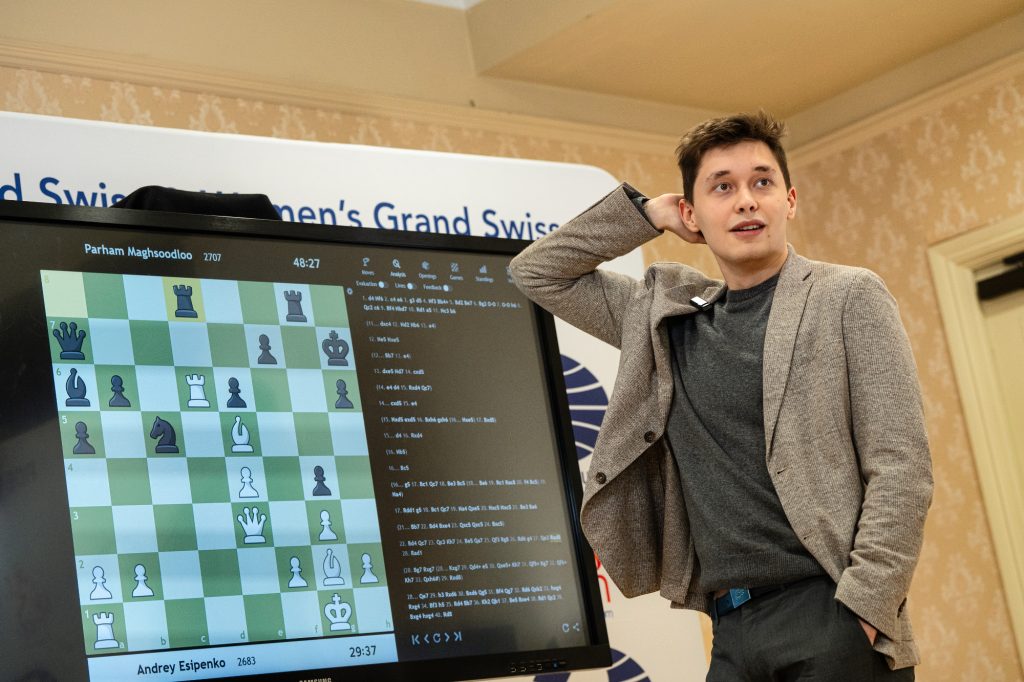

On board three Andrey Esipenko chose his favourite Catalan against Parham Maghsoodloo. Still, it was Black who chose a rare early on with 7…h6.

Moving the h-pawn is generally useful for Black, controlling the g5-square and waiting to see how White continues with development.

White chose the standard development with 8.Qc2 and 10.Bf4 and Black went down a line that is known from the move order when Black plays …b6 rather than …h6.

There was a subtle difference that was shown on move 16.

This position is known in theory, with Black having played …Bb7 and …Rc8 instead of …h6 and …a5. Maghsoodloo’s idea was that after 15…d4 16.Rxd4, he could play 16…g5 when the pawn on g5 would have extra protection.

However, in spite of playing a-tempo and having his preparation on the board, it was Black who messed things up.

Instead of 16…g5! 17.Bc1 Qc7 with a good position, Parham played 16…Bc5? 17.Rdd1 g5 18.Bc1 Qc7, but after 19.Na4! he ended up in a bad position because White took the bishop pair by taking on c5 and had the better structure.

A very unexpected waste of high-quality opening preparation!

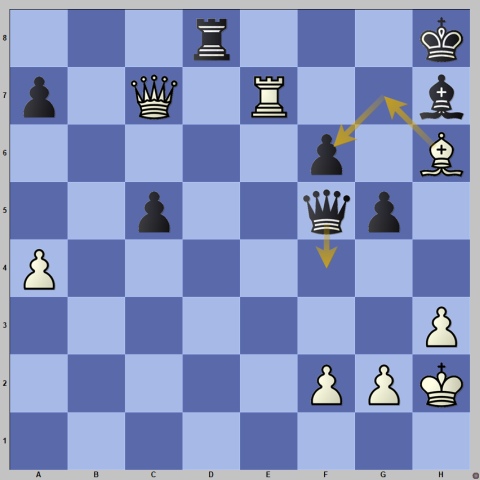

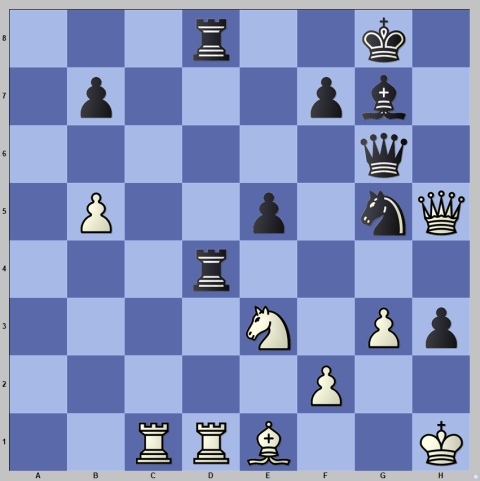

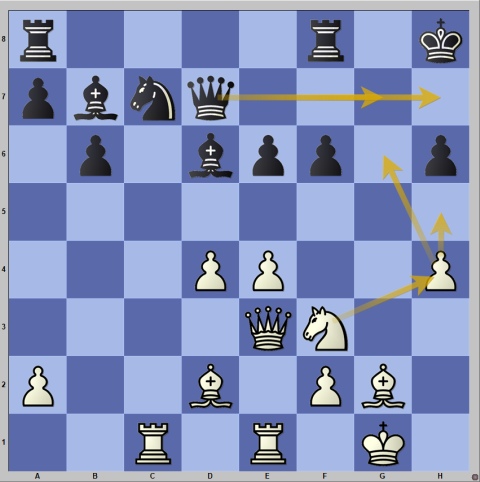

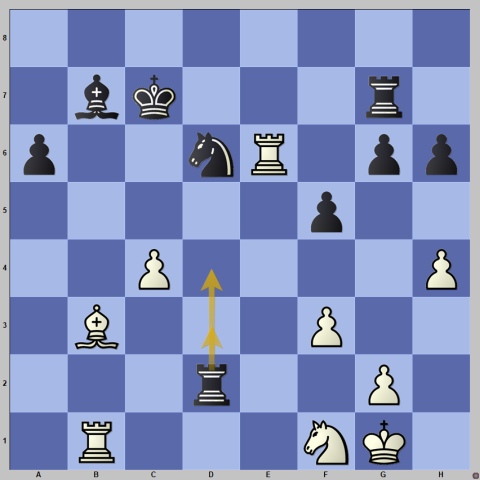

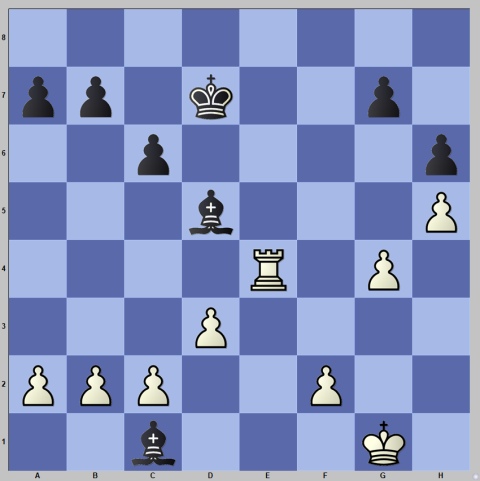

White methodically increased his advantage, and on move 28, he could have won with a beautiful combination.

After thinking for eight minutes, White played the natural 28.Rad1, which kept the advantage, but it wasn’t the best move. After the game, Esipenko admitted that he missed the beautiful 28.Bg7! The winning line was 28…Kxg7 29.Qd4 e5 30.Qxe5 Kh7 31.Qf5! and Black loses the rook on d8 after 31…Rg6 32.Rxd8 or is mated after 31…Kg7 32.Qf6.

White still had a sizable advantage because of Black’s weak king and White’s pair of bishops plus central domination.

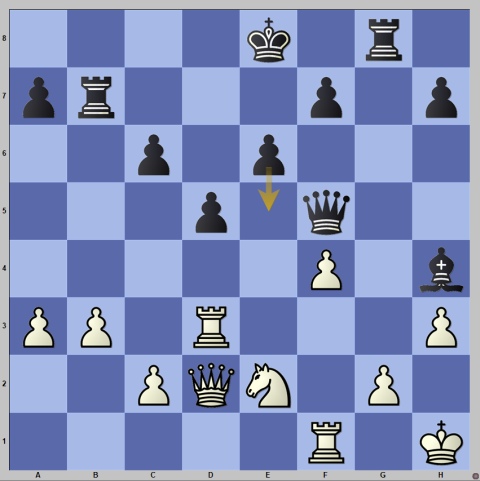

However, things got out of control as Black desperately sought counterplay. The decisive moment was on move 35. Despite having 24 minutes on the clock, Maghsoodloo didn’t manage to find the only move to stay in the game.

White’s last move 35. Rd4 was a mistake (35.Rd2 was winning), but White wanted to prevent the black queen from returning to the queenside. But here, Black could have played the insane-looking 35…Qxa2! and unexpectedly, White is not winning anymore. The lines are complicated, but the idea of the move is not so much about the pawn as is in the move …Qb3, possible only without a pawn on a2.

Black missed this chance and played 35…Bb7, but after 36.Kh2 Qb1 37.Be5 White was winning again, thanks to the threat of Rd8. When that move appeared on the board on move 40, Black resigned.

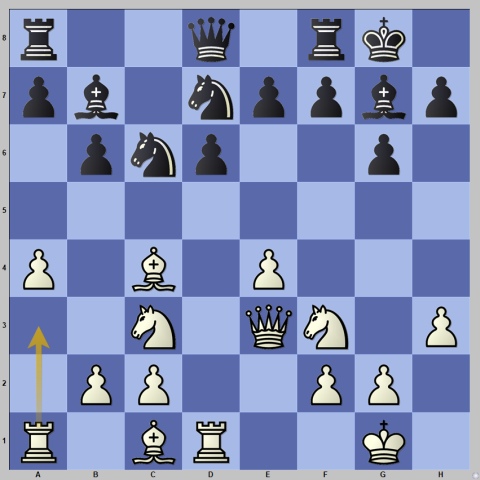

There was an early surprise, and on the same move (!), on board four as well. Vincent Keymer played the fianchetto variation in the Queen’s Indian and Vladimir Fedoseev opted for 7…Re8, a waiting move instead of the more direct 7…d5 or 7…Na6.

It is a waiting and preparatory move at the same time, as Black anticipates the opening of the e-file after …d5, cxd5 exd5.

White refrained from taking on d5 when he could exchange knights on that square because that would have given life to Black’s rook on e8. In the middlegame, White started kingside advance with h4 and g4.

With the queen on a4, White cannot hope for a realistic attack, but this advance increased the tension already present in the position.

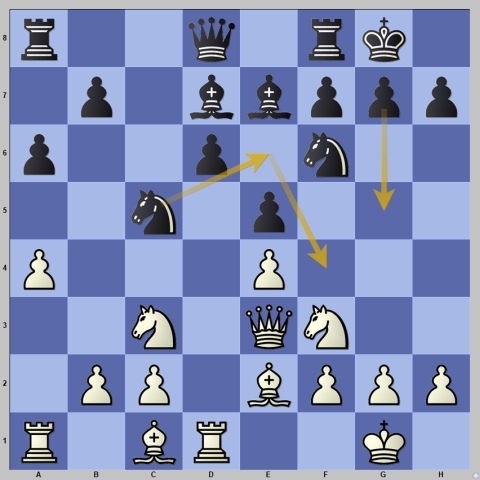

After Black removed the queen from the h4-d8 diagonal, White pushed g5 and opened the g-file. Play shifted to the kingside, where White could bring his queen via b3 to e3.

The position became very dangerous for Black as White intended h5 and Nh4-g6. The only way to stay somehow in the game was the queen maneuver 23…Qg7 with the idea to play …Qg4, when the queen’s presence on the kingside prevents White from creating an attack. Then White’s best would have been to exchange queens with Qh3, when the endgame is very promising for him.

Instead of this Fedoseev played 23…Qh7 with the idea to send the rook to g4, but after 24.h5 Rg8 25.Nh4, the knight made it to g6, and White could use it as a focal point of his attack. To make things even worse for Black, his rook on g4 was vulnerable to attacks.

Black somehow survived and even managed to run away with his king all the way to b8, but he lost the whole kingside and resigned in a lost endgame on move 49.

Hikaru Nakamura, Santosh Gujrathi Vidit and Andrey Esipenko lead with 7.5 points ahead of Alexandr Predke, Arjun Erigaisi and Vincent Keymer, who are half a point behind.

On board one in the women’s section Rameshbabu Vaishali didn’t shy away from her natural style of play, which is very tactical and dynamic, when she faced Tan Zhongyi’s Classical Sicilian. She boldly went for the Rauzer Attack and didn’t mind a sharp game. This likely suited her opponent as well because trailing by half a point gave her more chances to take over the lead by winning against the leader.

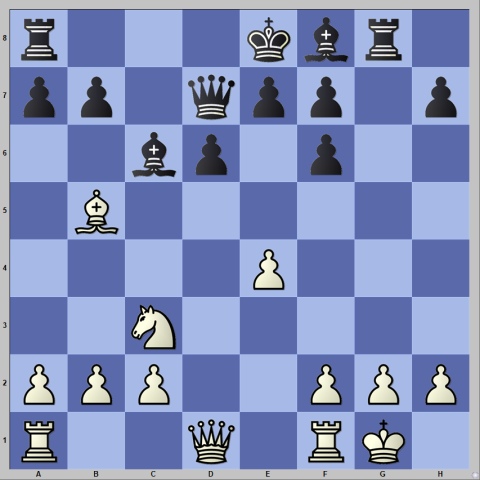

To show how meticulous is the opening preparation of the best players in the world, take a look at this position.

This rare position has been played only once before, in the online game between Leinier Dominguez and Richard Rapport. Not only did Vaishali know about this game, she even found the improvement of White’s play, which is to take on c6 and play f4 next.

White had an advantage in the middlegame thanks to her safer king, but the long-term prospects were in Black’s favour because of the heavy pawn presence in the centre and the possible advantage of a bishop over a knight. Therefore, it was surprising that Black didn’t exchange queens when she could have. This decision came back to haunt Tan Zhongyi.

Black’s king is unsafe in the centre in spite of the formidable pawn structure in front of it. Black’s decision to weaken it by 23…e5 looks extremely suspicious to a human, even though the engine claims Black can play this way.

In fact, the human factor became decisive as after 24.Re3 Re7? was already the crucial mistake; pushing …e4 was the only way to stay in the game. After 25.Qb4, the white queen found a way to attack the black king using the b-file.

White was already winning, and in the mutual time, trouble found the decisive maneuver.

White played 33.Nf4 with the decisive threat of Nxd5. Black barely survived to reach the time control, but resigned immediately afterwards.

In view of the results on the other boards, this victory ensured Vaishali a place in next year’s Candidates tournament!

On board two Anna Muzychuk faced Deysi Cori Tello. After 1.e4, Black went for the ultimate fighting and counterattacking choice by playing the Modern. In the Modern Black avoids immediate contact with White’s army by surrendering the centre, fianchettoing one (or sometimes both) bishops and only then attacking White’s centre by …b5-b4 (kicking away the knight on c3) and …c5.

White managed to stop …c5 by putting pressure on the d6-pawn, but Black obtained a typical counterattacking position, so she could be reasonably happy with the opening.

Instead of continuing in a controlled manner with 13.0-0 or 13.Bd2 White sacrificed a pawn after 13.c4 bxc3 14.bxc4 Nd7 15.Bd2 (15.exd6 was safer), and after Black took the pawn on e5, a murky position arose.

Neither king is entirely safe; White has a pair of bishops, but they are controlled by the centralised knights. At this moment, Black had less than 17 minutes for the 20 moves remaining until the time control.

The murky middlegame transposed to a murky endgame. The game took a turn in White’s favour on move 30.

From this moment on, Black started to play passive and defensive moves. Instead of 30…Ne3 she moved backwards with 30…Nd6. After 31.Rfe1, the counterattacking 31…f4 was correct, but Black again chose the passive 31…Rxc7 32.Re6 Rg7, but after 33.c4 White was firmly on top. The final mistake for Black came after 33…Kc7 34.Nf1.

Instead of latching onto the knight once it comes to e3 with 34…Rd3, thus threatening …Bc8, Black played the neutral 34…Rd4? when after 35.Ne3 White got a winning advantage, which she converted after the time control, winning on move 42.

On board three, Antoaneta Stefanova chose to take on d4 with the queen rather than the knight in the open Sicilian against Leya Garifullina. It’s one of the many ways White uses against the Sicilian to just obtain a playable position and get a game. This is what happened as both sides developed normally. At the start of the middlegame, the position resembled the Dragon variation because of Black’s fianchettoed bishop.

Here, White came up with the curious 12.Ra3!?. The move has several ideas – to remove the rook from the long diagonal, to activate the rook before the retreat Ba2 and to defend the knight on c3 in preparation for a possible b4.

The game became incredibly complicated, and it was Black who did better. After the time control, Leya could win in two moves.

The simple 41…Qh1 42.Kf2 Qb1 wins material for Black, and all White can do is resign.

Black played 41…Bc7, which was still winning, for example after 42.Qa1, as Stefanova played, and now 42…Bb6. The position remained won for Black, but she failed to finish it off and then misplayed her advantage and could only reach an equal endgame, which was drawn.

On board four Mai Narva faced Batkhuyag Munguntuul’s Caro-Kann. She went for the Two Knights variation, an early favourite of Bobby Fischer. In Fischer’s times, the line chosen by Black with 3…dxe4 4.Nxe4 Nf6 was not held in high regard, but nowadays, the positions after 5.Nxf6 exf6 are considered quite acceptable for Black.

Therefore, White didn’t take on f6 and played 5.Qe2 and after the exchange on e4 a typical Caro-Kann structure was reached.

White could have played better earlier, but going into this position, she was tempted by the sacrifice 17.Nxe6?! (17.Nf3 was both safer and better) fxe6 18.Bxe6 Rd7.

However, the sacrifice was in Black’s favour because White exchanged her two light squares, and the rooks couldn’t create serious threats along the only open e-file. Black managed to consolidate and stabilise the position, which went into an endgame on move 32.

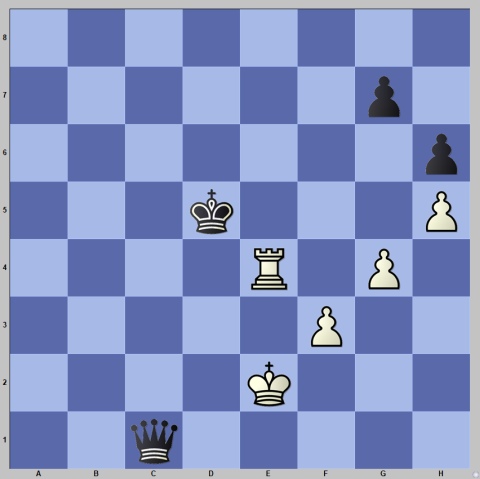

Black used the power of the bishops to attack White’s queenside. After the time control, Batkhuyag had a relatively straightforward way to win.

Going forward with the king after 43…Kb4, in order to land on c3 and surround the c2-pawn, would likely have won the game without too many issues. Black missed this idea, and the game dragged on.

Thanks to a tactic, Black managed to promote the b-pawn at the cost of her bishops, while White hoped to build a fortress.

The position is winning for Black, but it requires a lot of maneuvering. Black should use the queen’s power to put White in a zugzwang so she either lets the black king approach or leaves the f3-pawn vulnerable.

Eventually, White was forced to allow both. On move 90 Black finally crashed through by transposing to a winning pawn endgame.

After 90…Qf2+ 91.Ke4 Qe2 92.Kd3 Qxf3! the game was over.

Before the last round, Rameshbabu Vaishali leads with 8 points, ahead of Anna Muzychuk with 7.5 and Batkhuyag Munguntuul with 7.

Fans can follow the Grand Swiss 2023 by watching live broadcasts of the event on FIDE Youtube and Twitch with expert commentary by GM David Howell and IM Jovanka Houska.

Round 10 will be played on November 5.

Standings after Round 10 Women

Written by GM Alex Colovic

Photos: Anna Shtourman and Maria Emelianova/Chess.com

About the event:

The FIDE Grand Swiss and FIDE Women’s Grand Swiss 2023 takes place from the 23rd of October to the 6th of November at the Villa Marina, Douglas, Isle of Man.

Both tournaments are part of the qualifications for the World Championship cycle, with the top two players in the open event qualifying for the 2024 Candidates Tournament and the top two players in the Women’s Grand Swiss qualifying for the 2024 Women’s Candidates.

Eleven rounds will be played under the Swiss System, with 164 players participating from all continents: 114 in the Grand Swiss and 50 players in the Women’s Grand Swiss.

The total prize fund is $600,000, with $460,000 for the Grand Swiss and $140,000 for the Women’s Grand Swiss.

The first Grand Swiss was held in 2019 in the Isle of Man and was won by GM Wang Hao, who scored 8/11. The 2021 edition was moved from Isle of Man to Riga due to Covid restrictions on the island and was won by GM Alireza Firouzja.

This is the second time that a Women’s Grand Swiss event will be held. The inaugural edition in Riga was won by GM Lei Tingjie.